Boxing’s underbelly lies stagnant and yet dust still struggles to settle on the blue-and-white bags of Finchley Boxing Club.

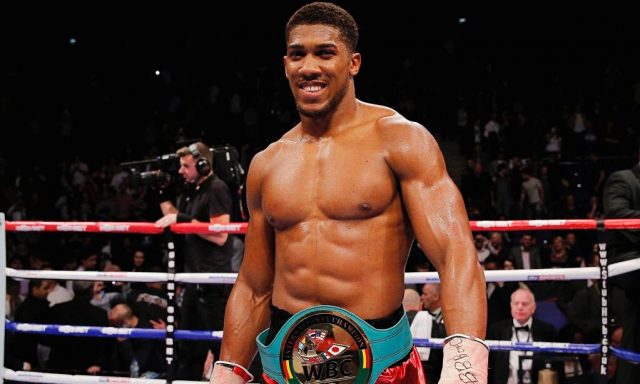

Outside, the mist shows little sign of lifting. Inside, Anthony Joshua is hunkering down for another round of house-sitting.

This corner of north London is where the heavyweight champion first laced gloves and where, for much of the past year, he has trained alone.

With the club’s current crop locked out by coronavirus, it’s up to AJ to keep the lights on.

Last month, after reading Sportsmail’s report from the Repton boxing club in East London, Joshua backed our campaign to save grassroots sport.

He made a donation to the sport’s amateur governing bodies in England, Wales and Scotland; Finchley was given its own slice of the pie, too. Just last week he was one of several fighters to support a Government petition for extra funds for grassroots boxing.

Back in north London, Sean Murphy is doing his bit, too. He coached AJ in those early days and through the fog of Covid, one thing has become clear: a trainer’s most vital corner work happens after the bell has stopped ringing.

‘I’ve got a few boys that are really struggling with their mental health,’ says Murphy. ‘They’re just lost without the boxing.’

One has missed its thudding rhythm more than most. ‘He was saying he felt like committing suicide because he couldn’t get to the gym,’ Murphy continues. ‘He’s seeing a doctor and, thankfully, it’s all right but a lot of these kids, they have nothing in their lives — boxing is all they have.’

And these are perilous times for the sport’s beating heart.

Few of Britain’s 1,300-odd amateur gyms were flush with cash even before coronavirus struck; those lucky enough to survive this second wave of misery will count the cost only once the doors creak back open. ‘Some of the kids are going to go somewhere else or do something else,’ Murphy fears.

‘Your teenage years — from 13 to 16, 17 — that’s when you’ve got to try and stay on the straight and narrow.’

He needs no reminding of the reward for keeping them there.

After all, among those to taste life on both sides of the track is this gym’s most famous son. Twice Joshua’s journey to heavyweight supremacy was nearly derailed. Twice Murphy dragged him back on course.

That’s why he is so concerned. And why AJ, backed by National Lottery funding before winning Olympic gold in 2012, has dipped into his own pocket to help. In less troubled times, he bought Finchley a new minibus and those club-coloured bags. Now he will help refurbish the weights room and possibly fund a new ring. A loan from the council has helped to sustain them, too. It all means that, unlike many clubs, Finchley are not counting their pennies. Instead the damage will be measured in squandered potential and fractured lives. ‘It’s hard because a lot of kids are saying to me, “When do you think we’re going to be boxing?” and I’ve got no idea,’ Murphy says. ‘I don’t even know if we’ll have a season this year.’

For AJ, too, it means more solitude. He had recently taken one of Finchley’s young welterweights, 16, under his wing.

During the first lockdown, when Murphy spent two weeks helping problem kids in nearby Borehamwood, Joshua spoke to the group over Zoom. And in the minutes after beating Kubrat Pulev last month, he spotted Murphy in the Wembley Arena crowd. ‘I’ll be popping in next week,’ he said.