Nigerians love their number one sport.

They also love their national football teams, particularly the Super Eagles, with a passion. The rest of the world appreciates what Nigerian players bring to the table of football – exuberance, speed, power and raw dribbling skills when they have the freedom to express them. The evidence is in the ceaseless hunt for the best Nigerian players all over the world. Forget about official statistics because they don’t reflect the true position with Nigeria. In 2020, at the rate Nigerian players are being shepherded abroad by agents and scouts, the country will be amongst the top 5 countries on earth with the most footballers outside their country.

Nigeria could be a truly great footballing nation, but the problem is that they do not treat and nurse their domestic football the way they should, otherwise, by 2020, Nigeria would have won the World Cup once, and be counted comfortably amongst the top ten countries in the world in all ramifications of the game! Instead, they handle their domestic football, the source of their strength, with levity and laxity.

Last weekend, another player died on the football field in Nigeria, again.

Forget about the official statistics, Nigeria may rank amongst the countries with the highest mortality rate of footballers dying on the field of play. I have been looking at some of the figures since Samuel Okwaraji, 31 years ago, plus our attitude to them. I am in shock.

Here in Nigeria, no one can be sure of the figures, but considering how ‘cheap’ dying has become, and how the death of a player would pale into insignificance in the sea of a thousand other deaths in a thousand other ways around the country, and how people have become so dehumanized, I will not be surprised if my assumption is true that we may hold that inglorious global record. The player that died last weekend was Chineme Martins. He played for one of the Premier League teams, Nassarawa United FC. He slumped and died. About a month before that another player had slumped and died too somewhere in the country on the training ground.

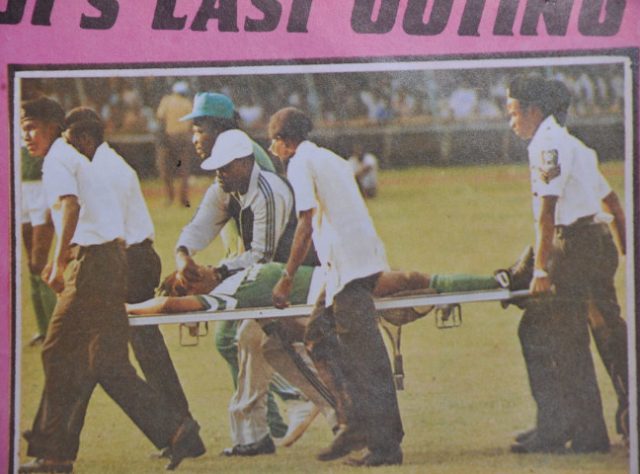

The most known case of an on-field death of a Nigerian was that of Samuel Okwaraji in 1989 during a World Cup qualifying match against Angola at the National Stadium in Lagos. Sam’s death was mysterious. A fit young man who had played some of the best matches of his career during that season simply slumped without any physical contact by anyone on the field, was immediately attended to by medical personnel, was rushed in an ambulance to the hospital, but died on the way there. On that fateful day, there were at least 6 specialist doctors on that field, plus a fully equipped and functional ambulance at the venue that eventually conveyed him to the hospital.

So, even with the best personnel and emergency facilities on ground, a player can die.

What was critical were the lessons to be learnt through the manner of his death to forestall a re-occurrence of such inn the future. Only an autopsy could reveal that. So, it was done. The strangest development to this day, 31 years later, is that no official autopsy report has been publicly released, or acted upon in order not to make Sam’s death be in vain. ‘The Cardiac arrest’ verdict on all official documents was not from the report of the autopsy. A few persons in the corridors of football may know, but, no lessons were learnt from his death that later impacted Nigerian football. That’s why there has never been a final ‘closure’ to his death. There are still unanswered questions that have denied the Nigerian football hero his full accolades, compensation and recognition that his service to the country and his performances on the football field deserved. So, without a template established to guide those responsible for Nigerian football, nothing happened when the cases of other players slumping and dying on the football field began to happen, including that of Amir Angwe at the Onikan Stadium, Lagos, in 1995, Charity Ikhidero in Benin in 1997, Orobosa Adun, John Ikoroma, Emmanuel Ogoli, and many other little-known players in smaller leagues all over the country.

Attitudinal change to such deaths only came following Emmanuel Ogoli’s death in December 2010 in Yenogoa, in disgraceful circumstances. Following pressure by the Nigerian media the NFA was forced to set up a special committee of medical experts, drawn from the Sports Ministry and medical institutions, to investigate the shameful incident. The committee concluded that Ogoli could have lived had there been the presence of any trained medical personnel, or even an ambulance to rush the player to the nearest hospital. The committee submitted a great report and made recommendations to the NFA on how to handle future accidents.

The report was very comprehensive, concluding that Yenogoa was only a reflection of the state of medical arrangements, personnel and facilities for players and for league matches generally, countrywide. There had not been any deliberate action by those in charge of football in the country to address the issues and to do everything to stem such tragedies.

So, for the years after Sam Okwaraji and before Emmanuel Ogoli, players died ‘cheaply’ on the field and no one took responsibility, and no one was held accountable. The families of the players would just bury their loved ones, shed their tears, and Nigerian football administrators will go on without missing a single beat. End of story. The report of that committee in 2011 gave rise to regulations within the NFA statutes that were adopted in the League Management Company’s regulations to clubs, to be complied with by all clubs. It covered insurance, annual tests for players, attestation of health status by qualified medical personnel, ambulances and qualified personnel at all match venues, and so on, all beautifully scripted and included in the league handbooks that were not enforced to the letter, nor supervised to the hilt. The NFF and their LMC, took things for granted, and since those deaths were rather infrequent, and no one was ever required to account for the few that happened, they went to ‘sleep’ over what should have been strict compliance, implementation and enforcement of the medical requirements for playing league matches.

They have been woken up from their slumber by the unusual reactions to Martin’s death last weekend that have been revealing gory details. For how Chineme was medically handled on the field after he slumped on that day some people should actually be in jail by now, held for complicity in a blatant ‘murder’. That the player died is not really the issue because death is an inevitability in every homo sapiens life, and ‘will come when it will come’. The real issue is that for a player that was dying on the field to be ‘mishandled’ in such an unprofessional manner by untrained hands in the absence of any trained medical personnel, and with no ambulance to convey him to the nearest hospital on time to be saved, can only be the product of neglect, administrative incompetence, dereliction of duty, ineptitude, carelessness and laxity. That is why Chineme’s death is raising quite some dust and has refused to go the way of the others before it.

Chineme’s death has now thrown the searchlight on not just the state of medical facilities and personnel in Nigerian professional football, but also on how very little attention is being paid to the details of organizing matches and how the organizing body does not take full responsibility when failures do occur. What has happened now is that the LMC has been jolted by the shocking video of the incident in Nassarawa, through the intervention of the new Sports Minister, and has started to castigate and punish everyone around it, but itself! The LMC is always willing to take full credit for its good works, but now seems to want to distance itself from a failure that has led to the death of a player. The LMC has sent condolence messages to the family of the deceased. They have sanctioned the club and the match official they appointed to handle the match. They have imposed a heavy fine on the club. Yet, one week after the death of the player, they are still setting up a committee to investigate what happened. The most important aspects of all this are the player (what happens to the player’s family), such should never happen again, and what the LMC itself now does itself. It must demonstrate capacity and competence to handle the multiple and daunting tasks of running the professional league beyond marketing the game and raising funds. Otherwise, its role in running football in Nigeria must be revisited and re-examined. Nigerians are watching very closely how this incident will finally pan out. Will another player simply die on the field and Nigerian domestic football will simply shrug it off and go on unperturbed? This may be one death too many, even for the League Management Company, LMC.